|

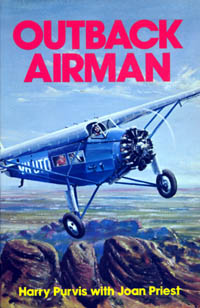

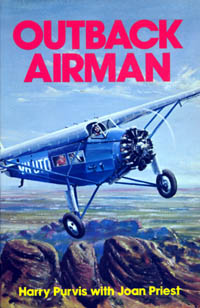

Harry

Purvis was one of the select few pilots trusted to fly the Southern

Cross for the film Smithy in 1945 and also when the

aeroplane made its final flight at an air pageant in 1947. He

recalled both occasions in his biography Outback Airman

written with Joan Priest and published by Rigby in 1979.

The Movie: (Pages 121-124)

Things were still fairly quiet at Morotai as we waited for a

new airstrip to be completed, when a message arrived from headquarters

informing me that the movie producer, Ken Hall, of Columbia

Pictures, had persuaded the Federal government to make the Southern

Cross available for a film to be based on the life of Sir Charles

Kingsford Smith. Scotty Allan and Bill Taylor were overseas

at the time and they wanted me to fly the Old Bus from Canberra

to Sydney for shooting the necessary film sequences. The Minister

for Air, Mr Drakeford, had authorised my release from active

service and, thoroughly delighted at the prospect, I flew to

Sydney on the next available aircraft.

My oId friend, John Kingsford-Smith, Smithy's nephew, also a

wing commander by now and at Merauke running the fighter sector,

had been given leave as well. He was to act as co-pilot and

we met in Sydney. ...

John had flown down from Merauke looking a shadow of his former

self, following recurrent bouts of malaria, but he was in high

spirits, like myself, at the prospect ahead. We were joined

by Harold Affleck, Smithy's original aircraftsman and DCA's

natural choice as their representative for the occasion, and

we flew to Duntroon where the Southern Cross was ready for its

first flight after ten years as a museum piece.

She was on the airstrip glittering in the morning sun, the fuselage

reconditioned and painted its original deep blue, with the wing,

engines and name picked out in silver. The RAAF Department of

Technical Services had detailed a special ground squad of twenty

men under Warrant Officer M. J. Burt to recondition the Old

Bus and weeks of intensive work had gone into the preparation.

The engines had been completely overhauled, the controls tested

thoroughly for smooth, efficient operation, and all the instruments

were fully operative. Now the big moment had arrived. The famous

old three-engined Fokker, in which Australia's most distinguished

airman had made so many pioneering flights, was to take to the

air again.

It was some forty-five minutes before we were scheduled to take

off and I walked out with the warrant officer past the assemblage

of VIPs, politicians, high-ranking public servants, top Air

Force brass, civil aviation personalities and prominent businessmen

- all awaiting the event. As we approached the Southern Cross,

shining in her refurbished glory, the warrant officer said,

'Well, sir, there she is. As good as we can make her'. Then

he added, 'There's just one thing that's got me puzzled.though.

Look at this'.

He walked over to the starboard engine and pointed to the propeller.

There, engraved clearly on the hub, was the word 'Unserviceable'.

I was completely flabbergasted. They say your sins will catch

up with you eventually and this looked like being the moment

when the old adage was coming true for me. It felt like the

crack of doom. To explain the situation, I shall have to remind

you of the barnstorming days with Smithy when a stone damaged

the starboard propeller and I flew to Sydney for a replacement

and, on return, asked for and was given the damaged prop as

a memento. (It is probably this damaged propeller that is mentioned

in John Kingsford-Smith's

autobiography.) And how, in 1935, when Smithy asked for

it back to make his final flight in the Old Bus which was minus

a prop since the trans-Tasman drama, he agreed instead to borrow

the spare metal propeller I had with my Fokker Universal and

let me keep my treasured memento. The condition was that I get

a perfect replica made and fitted to the Southern Cross in the

museum.

I'd gone immediately to George Adams, master propeller maker

in Sydney and told him what was needed. His usual charge for

making a propeller was £28 but as this one was for display purposes

only, I told him I wanted one at a cut-rate, a 'mock-up' job,

and offered him £5. George, a craftsman of the old school, was

quite incapable of turning out anything but a perfect job and

threw up his hands in horror at this proposition. Finally, as

I'd been a good customer of his, he agreed, on condition that

the hallowed name of 'Adams' did not appear on the prop and

that the word 'Unserviceable' be deeply stamped on the hub.

Of course I agreed to this; George made the 'display' propeller

and I kept my prized mantel souvenir.

This, then, was the situation that confronted me on the tarmac

at Duntroon. I had to fly the precious Southern Cross with a

'mock-up' propeller, made for display purposes, or disappoint

all the assembled dignitaries and the men who had worked on

her for weeks and cause some very red faces all round, including

my own. Representatives were there from all leading newspapers,

newsreel cameramen and radio commentators. I had a nasty, sinking

feeling in my stomach and sat down to figure things out.

A new propeller would take three weeks to make and I didn't

even know if George Adams was still functioning at his workshop

or if the drawings for a Fokker propeller of that type were

still available. Cursing my original skin-flintedness - why

hadn't I somehow found that £28 for a perfect prop? - I took

a good look at the 'unserviceable' one. It was made of laminated

Queensland maple, the same as the others but without the polish.

Looking at it, I firmly believed that master craftsman George

Adams could not make a bad propeller, even for museum use only.

But supposing, as could easily happen, I should go down in aviation

history as the man who wrecked the famous Southern Cross, knowing

it had one propeller which could have been considered unserviceable

and was, indeed, stamped as such? It was a tough decision to

have to make and I suffered some nerve-racking minutes before

I went and discussed it with John and Harold - the latter had

mended the wing in Palmerston North and knew the aircraft as

well as I did. The warrant officer told us that in ground tests

the 'unserviceable' prop was smoother than the others and had

given perfect revs. We decided we must put our trust in it.

Harold and the warrant officer were accompanying us on the flight.

As we took off to the cheers of that distinguished gathering,

none of whom was aware of the tense drama that was being enacted

before their eyes, and as the old Fokker soared smoothly up

and away, John and I didn't have to look at each other to know

we had another presence in the cockpit with us. How many dramas

had Smithy faced in her and always with fanatical faith?

The gamble we took in the pride and skill of Adams as a craftsman

paid off. The aircraft flew beautifully, reaching 160 kph with

ease, both then and on the flight to Sydney the following day,

and we made all the flights for the film with that propeller.

Australian actor Ron Randell starred as Smithy and Muriel Steinbeck

as his wife, Mary. To simulate Smithy's takeoff from Oakland,

California, in the historic east-west trans-Pacific flight of

1928, I flew the Old Bus over Bulli. I had also to fly her with

heavy banks of cloud, make landings and takeoffs and perform

other manoeuvres for the film. All these flying sequences were

shot by cameramen in an Avro Anson. For the studio sequences

a mock-up of the Southern Cross was erected by Cinesound craftsmen

and when Bill Taylor returned he was himself in the sequence

which showed him climbing out on the wing of the Fokker over

the Tasman Sea to make his epic oil change.

The Old Bus was stored away again after her role as film star

(supposedly never to fly again, though we did manage to reverse

that decision once as I shall relate) and I headed north for

the real world of war and transport squadrons once again.

Refer

Engines & Propellers

The

Bankstown Pageant - Pages 149-150:

After

the filming in 1945, the Minister for Air, Mr Drakeford, had

said that the old aircraft was not to fly again, but the New

South Wales Aero Club, staging a big air pageant at Bankstown,

persuaded him to authorise what was definitely, to quote Madame

Melba, 'her last appearance'. Again I was privileged to be her

pilot.

I flew the Old Bus from Mascot to Bankstown and the huge crowd

at the pageant gave her a tremendous ovation when I landed there.

I kept her stationary and well-guarded, close enough for the

crowds to get a good look at her but not close enough to touch,

let alone kick a tyre, the peculiarity that had been one of

the banes of Smithy's life.

Towards the end of the afternoon, as I prepared to take her

back to Mascot, Mr Drakeford told me he thought it would be

a good thing to show the Southern Cross, airborne for the last

time, to the people of Sydney. I took this as giving me unofficial

approval to wink a little at the low-flying regulations.

Alone in the famous old Fokker, I flew her as low as 200 feet

over Martin Place, over the harbour and some of the inner suburbs.

Over Palm Beach, near my home at Whale Beach, I flew down to

fifty feet, reviving memories of my barnstorming days and our

wave-hopping along the coast, and of the first surf patrol which

I'd flown for 2UW.

Over Pymble, I looked down and saw my daughter, Robyn, and her

friends at Presbyterian Ladies College waving from the school

grounds. She'd known I was to fly the Old Bus that afternoon

and they were looking out for me.

As I had flown over the city and suburbs I'd experienced a feeling

of elation, but as the sun set this was replaced by a sense

of melancholy. I had an almost overpowering illusion that Smithy

was there with me in the cockpit. I could see those piercing

blue eyes peering ahead into the gathering dusk to pick out

the runway on the aerodrome that was to bear his name, and to

which he had returned after so many epic flights. No one would

deny that there are some things beyond our ken, and who is to

say that Smithy's spirit was not present on that last flight

of the wonderful old aeroplane he had loved and flown so well?

This time, when the three engines stopped with their characteristic

clatter, it was really 'finished with engines', as the seamen

say. Later the Southern Cross was taken by road to Brisbane,

where she now rests, a museum-piece at Eagle Farm airport. I

always feel it is appropriate that she should remain there,

as Smithy was Queensland-born, and the people of his native

State have taken good care of what is almost certainly Australia's

most famous aircraft.

The Old Bus is there for anyone to see, only a few hundred metres

from where she came to rest after the great east-west crossing

of the Pacific in 1928.

|